Auto and Design

December 1995

In the original spirit

Author: Auto & Design - by Alberto Calliano - December 1995

Firstly, the make. Then, that mating of style and technology that is its essence, transposing into current idiom both the ideal and the excitement. This is the philosophy of the Lotus Elise, the roadster presented in prototype guise at the Frankfurt show. The Elise has no desire to be a simple ëfun carí, but a true driverís car, gratifying to use and not just to own.

The name, too, has a special significance: a tribute to the grand-daughter of Romano Artioli, chairman of the English company and champion of the project. A gesture almost evocative of other times and undeniably in tune with the carís appeal, which has its roots in an unforgettable past countersigned by the name of Colin Chapman.

In effect, it is Eliseís intent to represent a full-scale return to the principles that made the founder of Lotus world famous, bequeathing high profile results to the history of post-war motor racing and models become myth to automotive evolution.

It is a question, basically, of a few rules that go arm in arm with the quest for maximum returns demanded by racing: low weight and simplicity with a touch of elegance that must also, however, be function.

So, in August 1993 when Romano Artioli and Giampaolo Benedini - Director of Lotus styling - gave the go ahead to the development work, the brief did not contain dimensions or specifications, but outlined the philosophy: light weight, simplicity, innovation, jewel-like design, possibility of racing use, fun to drive.

Development of the styling was entrusted to the Lotus Design Studio, guided by Julian Thomson, many of whose members are the enthusiastic owners of sports cars and motorcycles. Thus began a period of frenetic activity that even ërobbedí the specialists of their weekends and saw the team orient itself towards a compact and minimalist two-seat vehicle: in short, almost a four-wheeled bike.

The Lotus Seven provided the emotive pull, but nobody wanted to create a pastiche that smacked of poor taste. Consequently, visual cues from the Lotus 23 and Lotus 40 racers were also carefully assessed. A ëcopyí was strictly forbidden, but the linking thread with the past was indispensable. Various possibilities were quickly analysed, including the ëformsí produced by mounting the engine at the front or in the centre, the preference going for the latter solution.

Simultaneously, the driving position and seating layout were examined along with the structure of the chassis, which from the very start was conceived as an independent element functioning as the anchorage for mechanicals and body: it was to be built in synthetic materials.

With this in mind, the man responsible for the chassis, Richard Rackham, who shares Julian Thomsonís passion for Ducati bikes, recognised that the structure should have a motorcycleís jewel-like design quality and started research in this direction. Thus was born the idea of the aluminium space frame.

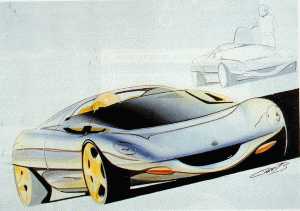

The first sketches came from Russell Carr in November, who initiated the idea of leaving the structure of the frame exposed inside the cabin and proposed a rear spoiler for a subsequent race version. Julian Thomson worked on a proposal where the bonnet housed an aggressive air intake, while a thin structure united windscreen with rear deck, providing a central mount for twin cabin protection elements.

The theme of the ëtopí was also tackled by the designers of Andrew Hillís team, who still, however, kept the accent on a bike-inspired, partially exposed, chassis. As each job was gradually completed, they were reviewed by Romano Artioli and Giampaolo Benedini who analysed the mix of past and present. What is clear, however, is that Lotus, like Ferrari and Porsche, has a tradition of style behind it that must not be ignored, even when faced - as in this case - with an advanced project of important technological worth.

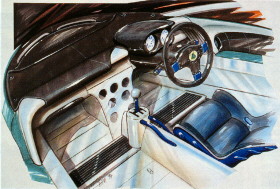

With this in mind, a further proposal by Russell Carr turned to the Lotus 23 for inspiraton, while the interior renderings developed by Andrew Hill and David Brisbourne highlighted the minimalism of the sports theme and definitively brought the frame centre stage as an element of cabin trim. Better to define the appropriateness of selected solutions, in February 1994 a review was organised with three scale models, sixty sketches from the Lotus Design team and over 160 proposals developed by Italian, Japanese and British design centres.

By the end of the same month the choice had gone for one of Thomsonís proposal which further refined the path taken by Andrew Hill, moving decidedly closer to what the final car would be. It was a two-seat sportster which demonstrated many classic features of the GT race cars of the 1960s: a sensuous form, with steeply raked wraparound windscreen, aggressive front end and roll-bar stylistically ëtiedí in to the rear deck.

For the cabin, a solution decidedly in tune with the carís spirit was designed: the absence of over-elaborate trim that would only have upped its weight; exposed frame elements to underline the sports feel; the inclusion only of components essential to the driver. Among other details, it was decided to anchor the passenger seat in the rearmost position. In the course of the following month it was also decided to equip the car with doors and a cabin-protecting hood. From scale models, the move was made to full-size mock-up, which was then exposed to a series of tests in the Mira wind tunnel; these indicated the need for a small spoiler at the rear in order to trim the carís aerodynamics at speed.

Meanwhile, development of the mechanical part was proceeding. In conjunction with Hydro Aluminium Automotive Structures, the space-frame hull was developed, weighing in at a mere 65 kilogrammes. It is completed by a steel subframe at the rear. With a view to obtaining the lowest weight possible, aluminium also finds use in some of the (double wishbone) suspension components and the ventilated disc brakes, a solution clearly derived from the competition world. In the same light, there is no brake servo.

For the engine, a 4-cylinder 16-valve 1.8 aluminium unit was earmarked, combined with a manual 5-speed gearbox. Centrally mounted in transverse position, it ëservesí the rear wheels via a transaxle setup.

By the end of 1994 the final touches had been made and the homologation process for the various markets was under way (USA excluded) with production expected at the rate of 700 units per year. The effort put into reducing the masses translates into an unladen weight of 675 kg, which offers tangible advantages in terms of handling, performance and fuel consumption: with the chosen engine (but the car could also ëacceptí others) the top speed is in fact estimated at 202 km/h with 5.9 secs from 0 to 100 km/h and 7.16 litres of fuel required for each 100 km at 120 km/h. But the ëfiguresí are of relative importance: the Elise, offers itself as a ëpureí two-seater that knows how to serve up excitement well beyond the spec-sheet.

Colin Chapman would approve.